Did Giotto Draw a Perfect Circle

| Giotto di Bondone | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Giotto di Bondone, fabricated between 1490 and 1550 | |

| Built-in | Giotto di Bondone c. 1267 near Florence, Democracy of Florence (present-day Italia) |

| Died | January 8, 1337(1337-01-08) (aged 69–seventy) Florence, Commonwealth of Florence |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Known for | Painting, fresco, architecture |

| Notable work | Scrovegni Chapel frescoes, Campanile |

| Movement | Late Gothic Proto-Renaissance |

Giotto di Bondone (Italian pronunciation: [ˈdʒɔtto di bonˈdoːne]; c. 1267 [a] – Jan 8, 1337),[2] [three] known mononymously as Giotto (,[iv] )[5] [6] and Latinised equally Giottus, was an Italian painter and architect from Florence during the Late Heart Ages. He worked during the Gothic/Proto-Renaissance period.[7] Giotto's contemporary, the banker and chronicler Giovanni Villani, wrote that Giotto was "the most sovereign master of painting in his time, who drew all his figures and their postures according to nature" and of his publicly recognized "talent and excellence".[8] Giorgio Vasari described Giotto as making a decisive interruption with the prevalent Byzantine style and as initiating "the not bad art of painting as we know it today, introducing the technique of drawing accurately from life, which had been neglected for more than 2 hundred years".[9]

Giotto's masterwork is the decoration of the Scrovegni Chapel, in Padua, besides known as the Arena Chapel, which was completed around 1305. The fresco bicycle depicts the Life of the Virgin and the Life of Christ. Information technology is regarded equally one of the supreme masterpieces of the Early Renaissance.[10] That Giotto painted the Arena Chapel and was chosen by the Commune of Florence in 1334 to blueprint the new campanile (bell tower) of the Florence Cathedral are among the few certainties near his life. Almost every other attribute of it is subject to controversy: his birth date, his birthplace, his appearance, his apprenticeship, the order in which he created his works, whether he painted the famous frescoes in the Upper Basilica of Saint Francis in Assisi, and his burial place.

Early life and career [edit]

One of the Legend of St. Francis frescoes at Assisi, the authorship of which is disputed.

Tradition holds that Giotto was born in a farmhouse, perhaps at Colle di Romagnano or Romignano.[xi] Since 1850, a tower house in nearby Colle Vespignano has borne a plaque claiming the honor of his birthplace, an exclamation that is commercially publicized. However, contempo research has presented documentary evidence that he was built-in in Florence, the son of a blacksmith.[12] His male parent's name was Bondone. Near authors accept that Giotto was his real proper noun, just it is likely to take been an abridgement of Ambrogio (Ambrogiotto) or Angelo (Angelotto).[1]

In his Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects Vasari states that Giotto was a shepherd male child, a merry and intelligent child who was loved by all who knew him. The great Florentine painter Cimabue discovered Giotto cartoon pictures of his sheep on a rock. They were so lifelike that Cimabue approached Giotto and asked if he could take him on equally an apprentice.[9] Cimabue was one of the two most highly renowned painters of Tuscany, the other being Duccio, who worked mainly in Siena. Vasari recounts a number of such stories about Giotto's skill as a young artist. He tells of one occasion when Cimabue was absent from the workshop, and Giotto painted a remarkably lifelike fly on a face in a painting of Cimabue. When Cimabue returned, he tried several times to brush the fly off.[xiii] Many scholars today are uncertain almost Giotto's grooming and consider Vasari'southward business relationship that he was Cimabue's educatee as legend; they cite earlier sources that suggest that Giotto was non Cimabue's educatee.[14] The story about the fly is also doubtable because it parallels Pliny the Elderberry'due south anecdote nigh Zeuxis painting grapes so lifelike that birds tried to peck at them.[fifteen]

Vasari besides relates that when Pope Benedict XI sent a messenger to Giotto, asking him to send a drawing to demonstrate his skill, Giotto drew a ruby circumvolve then perfect that it seemed as though it was drawn using a pair of compasses and instructed the messenger to send it to the Pope.[16] The messenger departed ill-pleased, believing that he had been made a fool of. The messenger brought other artists' drawings back to the Pope in addition to Giotto's. When the messenger related how he had made the circle without moving his arm and without the aid of compasses the Pope and his courtiers were amazed at how Giotto's skill greatly surpassed all of his contemporaries.[ix]

Around 1290 Giotto married Ricevuta di Lapo del Pela (known as 'Ciuta'), the daughter of Lapo del Pela of Florence. The marriage produced iv daughters and 4 sons, one of whom, Francesco, became a painter.[1] [17] Giotto worked in Rome in 1297–1300, merely few traces of his presence there remain today. By 1301, Giotto owned a firm in Florence, and when he was non traveling, he would return there and live in comfort with his family unit. Past the early on 1300s, he had multiple painting commissions in Florence.[16] The Archbasilica of St. John Lateran houses a minor portion of a fresco cycle, painted for the Jubilee of 1300 called by Boniface VIII. He as well designed the Navicella, a mosaic that decorated the facade of Sometime St Peter'southward Basilica. In this period Giotto also painted the Badia Polyptych, now in the Uffizi, Florence.[9]

Cimabue went to Assisi to paint several large frescoes at the new Basilica of Saint Francis of Assisi, and it is possible, but not certain, that Giotto went with him. The attribution of the fresco bicycle of the Life of St. Francis in the Upper Church has been one of the nigh disputed in art history. The documents of the Franciscan Friars that relate to artistic commissions during this menses were destroyed by Napoleon's troops, who stabled horses in the Upper Church of the Basilica, then scholars have debated the attribution to Giotto. In the absence of show to the opposite, it was convenient to attribute every fresco in the Upper Church not obviously by Cimabue to the more well-known Giotto, including thos frescoes now attributed to the Primary of Isaac. In the 1960s, fine art experts Millard Meiss and Leonetto Tintori examined all of the Assisi frescoes, and found some of the paint contained white atomic number 82—also used in Cimabue's badly deteriorated Crucifixion (c. 1283). No known works by Giotto comprise this medium. However, Giotto'southward panel painting of the Stigmatization of St. Francis (c. 1297) includes a motif of the saint holding up the collapsing church building, previously included in the Assisi frescoes.[18]

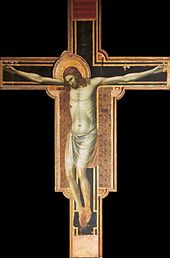

The authorship of a big number of console paintings ascribed to Giotto by Vasari, amid others, is as broadly disputed equally the Assisi frescoes.[19] According to Vasari, Giotto'due south earliest works were for the Dominicans at Santa Maria Novella. They include a fresco of The Annunciation and an enormous suspended Crucifix, which is about 5 metres (sixteen feet) high.[9] It has been dated to about 1290 and is thought to be gimmicky with the Assisi frescoes.[twenty] Earlier attributed works are the San Giorgio alla Costa Madonna and Child, at present in the Diocesan Museum of Santo Stefano al Ponte, Florence, and the signed panel of the Stigmatization of St. Francis housed in the Louvre.

The Crucifixion of Rimini

An early on biographical source, Riccobaldo of Ferrara, mentions that Giotto painted at Assisi merely does non specify the St Francis Cycle: "What kind of fine art [Giotto] made is testified to past works done by him in the Franciscan churches at Assisi, Rimini, Padua..."[21] Since the idea was put frontward by the High german fine art historian Friedrich Rintelen in 1912,[22] many scholars have expressed doubt that Giotto was the writer of the Upper Church frescoes. Without documentation, arguments on the attribution have relied upon connoisseurship, a notoriously unreliable "science",[23] just technical examinations and comparisons of the workshop painting processes at Assisi and Padua in 2002 have provided strong evidence that Giotto did not paint the St. Francis Cycle.[24] There are many differences between the Francis Cycle and the Arena Chapel frescoes that are hard to account for within the stylistic evolution of an individual creative person. Information technology is now generally accepted that four different hands are identifiable in the Assisi St. Francis frescoes and that they came from Rome. If this is the instance, Giotto's frescoes at Padua owe much to the naturalism of the painters.[one]

Giotto's fame as a painter spread. He was chosen to work in Padua and as well in Rimini, where in that location remains merely a Crucifix painted before 1309 and conserved in the Church building of St. Francis.[nine] Information technology influenced the rise of the Riminese school of Giovanni and Pietro da Rimini. Co-ordinate to documents of 1301 and 1304, Giotto by this time possessed large estates in Florence, and it is probable that he was already leading a large workshop and receiving commissions from throughout Italy.[1]

Scrovegni Chapel [edit]

Around 1305, Giotto executed his most influential work, the interior frescoes of the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua that in 2021 were alleged UNESCO World Heritage together with other 14th-century fresco cycles in different buildings around the city middle.[25] Enrico degli Scrovegni commissioned the chapel to serve as a family unit worship, burial space[26] and as a properties for an annually performed mystery play.[27]

The theme of the decoration is Salvation, and in that location is an emphasis on the Virgin Mary, as the chapel is dedicated to the Annunciation and to the Virgin of Charity. Every bit was common in church decoration of medieval Italy, the west wall is dominated by the Last Sentence. On either side of the chancel are complementary paintings of the angel Gabriel and the Virgin Mary, depicting the Annunciation. The scene is incorporated into the cycles of The Life of the Blessed Virgin Mary and The Life of Christ. Giotto's inspiration for The Life of the Virgin cycle was probably taken from The Golden Legend by Jacopo da Voragine and The Life of Christ draws upon the Meditations on the Life of Christ as well as the Bible. The frescoes are more than mere illustrations of familiar texts, yet, and scholars take found numerous sources for Giotto's interpretations of sacred stories.[28]

Vasari, drawing on a description by Giovanni Boccaccio, a friend of Giotto's, says of him that "in that location was no uglier man in the city of Florence" and indicates that his children were as well plainly in appearance. There is a story that Dante visited Giotto while he was painting the Scrovegni Chapel and, seeing the artist'due south children underfoot asked how a man who painted such cute pictures could accept such patently children. Giotto, who according to Vasari was always a wit, replied, "I brand my pictures by solar day, and my babies by night."[ix] [16]

Sequence [edit]

The cycle is divided into 37 scenes, arranged effectually the lateral walls in three tiers, starting in the upper annals with the story of St. Joachim and St. Anne, the parents of the Virgin, and continuing with her early life. The life of Jesus occupies two registers. The top south tier deals with the lives of Mary's parents, the top north with her early life and the entire center tier with the early life and miracles of Christ. The bottom tier on both sides is concerned with the Passion of Christ. He is depicted mainly in contour, and his eyes point continuously to the right, perhaps to guide the viewer onwards in the episodes. The buss of Judas near the end of the sequence signals the shut of this left-to-right procession. Below the narrative scenes in colour, Giotto too painted allegories of seven Virtues and their counterparts in monochrome grey (grisaille). The grisaille frescoes are painted to wait like marble statues that personify Virtues and Vices. The central allegories of Justice and Injustice oppose two specific types of government: peace leading to a festival of Dearest and tyranny resulting in wartime rape.[29] Betwixt the narrative scenes are quatrefoil paintings of Erstwhile Testament scenes, similar Jonah and the Whale, that allegorically correspond to and perhaps foretell the life of Christ.

Much of the blue in the frescoes has been worn away by fourth dimension. The expense of the ultramarine blue pigment used required information technology to exist painted on top of the already-dry fresco (a secco) to preserve its brilliance. That is why it has disintegrated faster than the other colours, which were painted on wet plaster and have bonded with the wall.[30] An example of the decay tin can conspicuously be seen on the robe of the Virgin, in the fresco of the Nativity.

Style [edit]

Giotto'due south fashion drew on the solid and classicizing sculpture of Arnolfo di Cambio. Unlike those by Cimabue and Duccio, Giotto'south figures are not stylized or elongated and exercise not follow Byzantine models. They are solidly three-dimensional, have faces and gestures that are based on close observation, and are clothed, not in swirling formalized drapery, but in garments that hang naturally and have form and weight. He also took assuming steps in foreshortening and with having characters face up inward, with their backs towards the observer, creating the illusion of space. The figures occupy compressed settings with naturalistic elements, often using forced perspective devices so that they resemble stage sets. This similarity is increased by Giotto'south careful arrangement of the figures in such a way that the viewer appears to accept a particular identify and even an involvement in many of the scenes. That tin be seen near markedly in the arrangement of the figures in the Mocking of Christ and Lamentation in which the viewer is bidden past the limerick to go mocker in one and mourner in the other.

Giotto's depiction of the human face and emotion sets his piece of work autonomously from that of his contemporaries. When the disgraced Joachim returns sadly to the hillside, the two young shepherds look sideways at each other. The soldier who drags a babe from its screaming female parent in the Massacre of the Innocents does so with his head hunched into his shoulders and a look of shame on his face. The people on the road to Arab republic of egypt gossip about Mary and Joseph as they get. Of Giotto's realism, the 19th-century English critic John Ruskin said, "He painted the Madonna and St. Joseph and the Christ, yeah, by all means... merely essentially Mamma, Papa and Baby".[1]

Famous narratives in the series include the Adoration of the Magi, in which a comet-like Star of Bethlehem streaks across the sky. Giotto is thought to have been inspired by the 1301 appearance of Halley'due south comet, which led to the proper name Giotto being given to a 1986 space probe to the comet.

Mature works [edit]

Details of figures from the Raising of Drusiana in the Peruzzi Chapel

Giotto worked on other frescoes in Padua, some now lost, such every bit those that were in the Basilica of. St. Anthony[31] and the Palazzo della Ragione.[32] Numerous painters from northern Italia were influenced by Giotto'due south work in Padua, including Guariento, Giusto de' Menabuoi, Jacopo Avanzi, and Altichiero.

From 1306 to 1311 Giotto was in Assisi, where he painted the frescoes in the transept expanse of the Lower Church of the Basilica of St. Francis, including The Life of Christ, Franciscan Allegories and the Magdalene Chapel, cartoon on stories from the Golden Legend and including the portrait of Bishop Teobaldo Pontano, who commissioned the work. Several assistants are mentioned, including Palerino di Guido. The style demonstrates developments from Giotto's piece of work at Padua.[1]

In 1311, Giotto returned to Florence. A document from 1313 about his article of furniture there shows that he had spent a period in Rome sometime beforehand. Information technology is at present thought that he produced the blueprint for the famous Navicella mosaic for the courtyard of the Old St. Peter's Basilica in 1310, deputed by Cardinal Giacomo or Jacopo Stefaneschi and at present lost to the Renaissance church except for some fragments and a Baroque reconstruction. Co-ordinate to the primal's necrology, he as well at to the lowest degree designed the Stefaneschi Triptych (c. 1320) , a double-sided altarpiece for St. Peter's, now in the Vatican Pinacoteca. It shows St Peter enthroned with saints on the front, and on the contrary, Christ is enthroned, framed with scenes of the martyrdom of Saints Peter and Paul. It is ane of the few works past Giotto for which house testify of a commission exists.[33] However, the manner seems unlikely for either Giotto or his normal Florentine administration so he may have had his pattern executed by an ad hoc workshop of Romans.[34]

The cardinal also deputed Giotto to decorate the alcove of St. Peter's Basilica with a cycle of frescoes that were destroyed during the 16th-century renovation. According to Vasari, Giotto remained in Rome for six years, afterward receiving numerous commissions in Italy, and in the Papal seat at Avignon, only some of the works are now recognized to exist past other artists.

In Florence, where documents from 1314 to 1327 attest to his financial activities, Giotto painted an altarpiece, known equally the Ognissanti Madonna, which is now on brandish in the Uffizi, where it is exhibited beside Cimabue's Santa Trinita Madonna and Duccio's Rucellai Madonna.[1] The Ognissanti altarpiece is the only panel painting by Giotto that has been universally accustomed by scholars, despite the fact that it is undocumented. It was painted for the church of the Ognissanti (all saints) in Florence, which was built by an obscure religious guild, known as the Humiliati.[35] Information technology is a large painting (325 x 204 cm), and scholars are divided on whether information technology was fabricated for the main chantry of the church, where it would take been viewed primarily by the brothers of the society, or for the choir screen, where it would have been more easily seen by a lay audience.[36]

He also painted effectually the fourth dimension the Dormition of the Virgin, now in the Berlin Gemäldegalerie, and the Crucifix in the Church building of Ognissanti.[37]

The Nascency in the Lower Church, Assisi

Peruzzi and Bardi Chapels at Santa Croce [edit]

According to Lorenzo Ghiberti, Giotto painted chapels for iv different Florentine families in the church of Santa Croce, but he does not place which chapels.[38] Information technology is only with Vasari that the 4 chapels are identified: the Bardi Chapel (Life of St. Francis), the Peruzzi Chapel (Life of St. John the Baptist and St. John the Evangelist, maybe including a polyptych of Madonna with Saints at present in the Museum of Art of Raleigh, North Carolina) and the lost Giugni Chapel (Stories of the Apostles) and the Tosinghi Spinelli Chapel (Stories of the Holy Virgin).[39] Every bit with almost everything in Giotto'due south career, the dates of the fresco decorations that survive in Santa Croce are disputed. The Bardi Chapel, immediately to the right of the chief chapel of the church, was painted in true fresco, and to some scholars, the simplicity of its settings seems relatively close to those of Padua, but the Peruzzi Chapel's more circuitous settings suggest a later date.[40]

Giotto, Peruzzi Altarpiece, c.1322, North Carolina Museum of Art

The Peruzzi Chapel is adjacent to the Bardi Chapel and was largely painted a secco. The technique, quicker merely less durable than truthful fresco, has left the piece of work in a seriously-deteriorated condition. Scholars who date the cycle earlier in Giotto's career see the growing involvement in architectural expansion that information technology displays as close to the developments of the giottesque frescoes in the Lower Church building at Assisi, but the Bardi frescoes have a new softness of color that indicates the artist going in a different direction, probably under the influence of Sienese art so it must be subsequently.[41]

The Peruzzi Chapel pairs three frescoes from the life of St. John the Baptist (The Annunciation of John's Nativity to his male parent Zacharias; The Birth and Naming of John; The Feast of Herod) on the left wall with 3 scenes from the life of St. John the Evangelist (The Visions of John on Ephesus; The Raising of Drusiana; The Rise of John) on the right wall. The choice of scenes has been related to both the patrons and the Franciscans.[42] Because of the deteriorated condition of the frescoes, it is difficult to hash out Giotto's fashion in the chapel, merely the frescoes show signs of his typical interest in controlled naturalism and psychological penetration.[43] The Peruzzi Chapel was particularly renowned during Renaissance times. Giotto'south compositions influenced Masaccio's frescos at the Brancacci Chapel, and Michelangelo is also known to take studied them.

The Bardi Chapel depicts the life of St. Francis, following a like iconography to the frescoes in the Upper Church building at Assisi, dating from 20 to 30 years earlier. A comparing shows the greater attention given by Giotto to expression in the human being figures and the simpler, better-integrated architectural forms. Giotto represents only seven scenes from the saint'south life, and the narrative is arranged somewhat unusually. The story starts on the upper left wall with St. Francis Renounces his Father. Information technology continues across the chapel to the upper correct wall with the Approval of the Franciscan Dominion, moves down the right wall to the Trial past Burn down, across the chapel again to the left wall for the Advent at Arles, downwardly the left wall to the Death of St. Francis, and across once more to the posthumous Visions of Fra Agostino and the Bishop of Assisi. The Stigmatization of St. Francis, which chronologically belongs between the Advent at Arles and the Death, is located exterior the chapel, above the entrance arch. The arrangement encourages viewers to link scenes together: to pair frescoes beyond the chapel space or relate triads of frescoes forth each wall. The linkings suggest meaningful symbolic relationships between different events in St. Francis's life.[44]

Later works and expiry [edit]

Engraving afterwards a portrait of Dante by Giotto

In 1328 the altarpiece of the Baroncelli Chapel, Santa Croce, Florence, was completed. Previously ascribed to Giotto, information technology is now believed to be generally a piece of work past assistants, including Taddeo Gaddi, who afterwards frescoed the chapel.[45] The next year, Giotto was called by Male monarch Robert of Anjou to Naples where he remained with a group of pupils until 1333. Few of Giotto'due south Neapolitan works accept survived: a fragment of a fresco portraying the Lamentation of Christ in the church building of Santa Chiara and the Illustrious Men that is painted on the windows of the Santa Barbara Chapel of Castel Nuovo, which are unremarkably attributed to his pupils. In 1332, Rex Robert named him "commencement court painter", with a yearly pension. Besides in this time period, co-ordinate to Vasari, Giotto composed a series on the Bible; scenes from the Book of Revelation were based on ideas by Dante.[46]

Later on Naples, Giotto stayed for a while in Bologna, where he painted a Polyptych for the church of Santa Maria degli Angeli and, according to some sources, a lost ornamentation for the Chapel in the Cardinal Legate's Castle.[9] In 1334, Giotto was appointed main builder to Florence Cathedral. He designed the bell tower, known every bit Giotto'due south Campanile, begun on July 18, 1334. It was not completed entirely to his design.[1] Before 1337, he was in Milan with Azzone Visconti, merely no trace of works by him remain in the city. His last known work was with assistants' help: the decoration of Podestà Chapel in the Bargello, Florence.[one]

In his terminal years, Giotto had become friends with Boccaccio and Sacchetti, who featured him in their stories. Sacchetti recounted an incident in which a civilian deputed Giotto to pigment a shield with his coat of arms; Giotto instead painted the shield "armed to the teeth", consummate with a sword, lance, dagger, and arrange of armor. He told the man to "Become into the earth a footling, earlier you lot talk of arms as if you lot were the Duke of Bavaria," and in response was sued. Giotto countersued and won two florins.[47] In The Divine Comedy, Dante acknowledged the greatness of his living gimmicky by the words of a painter in Purgatorio (Xi, 94–96): "Cimabue believed that he held the field/In painting, and at present Giotto has the cry,/ Then the fame of the one-time is obscure."[x] Giotto died in January 1337.

Burial and legacy [edit]

According to Vasari,[9] Giotto was buried in the Cathedral of Florence, on the left of the entrance and with the spot marked by a white marble plaque. According to other sources, he was buried in the Church of Santa Reparata. The apparently-contradictory reports are explained by the fact that the remains of Santa Reparata are directly beneath the Cathedral and the church continued in employ while the construction of the cathedral proceeded in the early on 14th century.

During an earthworks in the 1970s, bones were discovered below the paving of Santa Reparata at a spot shut to the location given by Vasari merely unmarked on either level. Forensic test of the bones past anthropologist Francesco Mallegni and a team of experts in 2000 brought to low-cal some testify that seemed to confirm that they were those of a painter (peculiarly the range of chemicals, including arsenic and lead, both usually found in paint, which the bones had captivated).[48] The basic were those of a very short man, little over four feet alpine, who may accept suffered from a form of congenital dwarfism. That supports a tradition at the Church building of Santa Croce that a dwarf who appears in one of the frescoes is a self-portrait of Giotto. On the other manus, a man wearing a white hat who appears in the Last Sentence at Padua is as well said to exist a portrait of Giotto. The appearance of this human conflicts with the image in Santa Croce, in regards to stature.[48]

Forensic reconstruction of the skeleton at Santa Reperata showed a short human being with a very big head, a large hooked nose and one heart more prominent than the other. The bones of the neck indicated that the human being spent a lot of time with his head tilted backwards. The front teeth were worn in a way consistent with frequently holding a brush betwixt the teeth. The man was virtually 70 at the time of expiry.[48] While the Italian researchers were convinced that the body belonged to Giotto and it was reburied with honour well-nigh the grave of Filippo Brunelleschi, others have been highly sceptical.[49] Franklin Toker, a professor of art history at the University of Pittsburgh, who was present at the original earthworks in 1970, says that they are probably "the bones of some fat butcher".[50]

References [edit]

Footnotes

- ^ The year of his birth is calculated from the fact that Antonio Pucci, the boondocks crier of Florence, wrote a poem in Giotto's honour in which it is stated that he was 70 at the fourth dimension of his expiry. However, the give-and-take "seventy" fits into the rhyme of the poem improve than any longer and more than complex age so it is possible that Pucci used artistic license.[one]

Citations

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Sarel Eimerl, The World of Giotto, Fourth dimension-Life Books.

- ^ "Giotto'south date of birth differs widely in the sources, but modern fine art historians consider 1267 to be the most plausible, although the years up to 1275 cannot be entirely discounted." Wolf, Norbert (2006). Giotto di Bondone, 1267–1337: The Renewal of Painting. Hong Kong: Taschen. p. 92. ISBN 978-3822851609

- ^ Giotto at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ "Giotto". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved June i, 2019.

- ^ "Giotto" (United states of america) and "Giotto". Oxford Dictionaries UK English language Lexicon. Oxford University Printing. n.d. Retrieved June 1, 2019.

- ^ "Giotto". Merriam-Webster Dictionary . Retrieved June 1, 2019.

- ^ Hodge, Susie (November 2016). Art in Detail: 100 Masterpieces (i ed.). New York: Thames & Hudson. p. 10. ISBN978-0-500-23954-four.

He worked during the catamenia described as Gothic or Pre-Renaissance ...

- ^ Bartlett, Kenneth R. (1992). The Civilization of the Italian Renaissance. Toronto: D.C. Heath and Company. ISBN 0-669-20900-7 (Paperback). p. 37.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the Artists, trans. George Bull, Penguin Classics, (1965), pp. 15–36

- ^ a b Hartt, Frederick (1989). Fine art: a history of painting, sculpture, architecture. Harry Due north. Abrams. pp. 503–506.

- ^ Sarel Eimerl, see beneath, cites Colbzs le di Romagnano. Notwithstanding, the spelling is perhaps wrong, and the location referred to may be the site of the present Trattoria di Romignano, in a village of farmhouses in the Mugello region.

- ^ Michael Viktor Schwarz and Pia Theis, "Giotto's Father: Erstwhile Stories and New Documents", Burlington Mag, 141 (1999) 676–677 and idem, Giottus Pictor. Band 1: Giottos Leben, Vienna, 2004

- ^ Eimerl 1967, p. 85.

- ^ Hayden B.J. Maginnis, "In Search of an Artist," in Anne Derbes and Marking Sandona, The Cambridge Companion to Giotto, Cambridge, 2004, 12-13.

- ^ Dalivalle, Antonia (10 May 2019). "Giotto's Wing and the Birth of the Renaissance | The Cultural Me". thecultural.me. Recreyo Ltd. Retrieved 20 September 2021.

- ^ a b c Eimerl 1967, p. 106.

- ^ Giotto, and Edi Baccheschi (1969). The complete paintings of Giotto. New York: H.Due north. Abrams. p. 83. OCLC 2616448

- ^ Eimerl 1967, pp. 95, 106–7.

- ^ Maginnis, "In Search of an Artist", 23–28.

- ^ In 1312, the will of Ricuccio Pucci leaves funds to go on a lamp burning before the crucifix "past the illustrious painter Giotto". Ghiberti also cites information technology as a work past Giotto.

- ^ Sarel. A. Teresa Hankey, "Riccobaldo of Ferraro and Giotto: An Update," Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, 54 (1991) 244.

- ^ Friedrich Rintelen, Giotto und die Giotto-apokryphen, (1912)

- ^ Come across, for case, Richard Offner's famous article of 1939, "Giotto, non-Giotto", conveniently collected in James Stubblebine, Giotto: The Arena Chapel Frescoes, New York, 1969 (reissued 1996), 135–155, which argues against Giotto'southward authorship of the frescoes. In dissimilarity, Luciano Bellosi, La pecora di Giotto, Turin, 1985, calls each of Offner's points into question.

- ^ Bruno Zanardi, Giotto e Pietro Cavallini: La questione di Assisi e il cantiere medievale della pittura a fresco, Milan 2002; Zanardi provides an English synopsis of his study in Anne Derbes and Marker Sandona, The Cambridge Companion to Giotto, New York, 2004, 32–62.

- ^ UNESCO. "Padua'southward fourteenth-century fresco cycles, UNESCO announcement". UNESCO . Retrieved fifteen August 2021.

- ^ See the complaint of the Eremitani monks in James Stubblebine, Giotto: The Arena Chapel Frescoes, New York, 1969, 106–107 and an analysis of the commission by Benjamin G. Kohl, "Giotto and his Lay Patrons", in Anne Derbes and Marking Sandona, The Cambridge Companion to Giotto, Cambridge, 2004, 176–193.

- ^ Schwarz, Michael Viktor, "Padua, its Arena, and the Arena Chapel: a liturgical ensemble," in Periodical of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes Vol. 73, 2010, 39–64.

- ^ Anne Derbes and Mark Sandona, The Usurer's Heart: Giotto, Enrico Scrovegni, and the Arena Chapel in Padua, University Park, 2008; Laura Jacobus,Giotto and the Arena Chapel: Art, Compages and Experience, London, 2008; Andrew Ladis, Giotto's O: Narrative, Figuration, and Pictorial Ingenuity in the Loonshit Chapel, Academy Park, 2009

- ^ Kérchy, Anna; Liss, Attila; Szönyi, György East., eds. (2012). The Iconology of Police force and Order (Legal and Catholic). Szeged: JATEPress. ISBN978-963-315-076-four.

- ^ Wolf, Norbert (2006). Giotto. Hong Kong; Taschen. p. 34. ISBN 3822851604.

- ^ The remaining parts (Stigmata of St. Francis, Martyrdom of Franciscans at Ceuta, Crucifixion and Heads of Prophets) are most likely from assistants.

- ^ Finished in 1309 and mentioned in a text from 1350 by Giovanni da Nono. They had an astrological theme, inspired past the Lucidator, a treatise famous in the 14th century.

- ^ Gardner, Julian (1974). "The Stefaneschi Altarpiece: A Reconsideration". Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes. 37: 57–103. doi:10.2307/750834. JSTOR 750834. S2CID 195043668.

- ^ White, 332, 343

- ^ La 'Madonna d'Ognissanti' di Giotto restaurata, Florence, 1992; Julia I. Miller and Laurie Taylor-Mitchell, "The Ognissanti Madonna and the Humiliati Gild in Florence", in The Cambridge Companion to Giotto, ed. Anne Derbes and Mark Sandona, Cambridge, 2004, 157–175.

- ^ Julian Gardner, "Altars, Altarpieces and Art History: Legislation and Usage," in Italian Altarpieces, 1250–1500, ed. Eve Borsook and Fiorella Gioffredi, Oxford, 1994, 5–39; Irene Hueck, "Le opere di Giotto per la chiesa di Ognissanti," in La 'Madonna d'Ognissanti' di Giotto restaurata, Florence, 1992, 37–44.

- ^ Duncan Kennedy, Giotto's Ognissanti Crucifix brought back to life, BBC News, 2010-11-05. Accessed 2010-11-07

- ^ Ghiberti, I commentari, ed. O Morisani, Naples 1947, 33.

- ^ Giorgio Vasari, Le vite de' più eccellenti architetti, pittori, et scultori Italiani ed. 1000. Milanesi, Florence, 1878, I, 373–374.

- ^ L. Tintori and E. Borsook, The Peruzzi Chapel, Florence, 1965, 10; J. White, Fine art and Compages in Italy, Baltimore, 1968, 72f.

- ^ C. Brandi, Giotto, Milan, 1983, 185–186; L.Bellosi, Giotto, Florence, 1981, 65, 71.

- ^ Tintori and Borsook; Laurie Schneider Adams, "The Iconography of the Peruzzi Chapel". L'Arte, 1972, one–104. (Reprinted in Andrew Ladis ed., Giotto and the World of Early Italian Art New York and London 1998, three, 131–144); Julie F. Codell, "Giotto's Peruzzi Chapel Frescoes: Wealth, Patronage and the Earthly Urban center," Renaissance Quarterly, 41 (1988) 583–613.

- ^ Long, Jane C. (2011). "xi. Parallelism in Giotto's Santa Croce Frescoes". Parallelism in Giotto's Santa Croce Frescoes. Push Me, Pull You. Brill. pp. 327–353. doi:10.1163/9789004215139_032. ISBN978-9004215139. .

- ^ The concept of such linkings was commencement suggested for Padua by Michel Alpatoff, "The Parallelism of Giotto's Padua Frescoes", Art Bulletin, 39 (1947) 149–154. Information technology has been tied to the Bardi Chapel by Jane C. Long, "The Programme of Giotto's Saint Francis Cycle at Santa Croce in Florence", Franciscan Studies 52 (1992) 85–133 and William R. Cook, "Giotto and the Figure of St. Francis", in The Cambridge Companion to Giotto, ed. A. Derbes and M. Sandona, Cambridge, 2004, 135–156.

- ^ Giotto, Andrew Martindale, and Edi Baccheschi (1966). The Complete Paintings of Giotto. New York: Harry N. Abrams. p. 118. OCLC 963830818.

- ^ Eimerl 1967, p. 158.

- ^ Eimerl 1967, p. 135.

- ^ a b c IOL, September 22, 2000

- ^ "Critics slam Giotto burial equally a grave mistake". Business Report. Independent Online. Sapa-AP. 8 January 2001.

- ^ Johnston, Bruce (six Jan 2001). "Skeleton riddle threatens Giotto'southward reburial". Telegraph.co.great britain . Retrieved 23 March 2018.

Sources [edit]

- Eimerl, Sarel (1967). The Globe of Giotto: c. 1267–1337 . et al. Time-Life Books. ISBN0-900658-fifteen-0.

- Previtali, G. Giotto east la sua bottega (1993)

- Vasari, Giorgio. Le vite de più eccellenti pittori, scultori e architetti (1568)

- — —. Lives of the Artists, trans. George Bull, Penguin Classics, (1965) ISBN 0-14-044164-6

- White, John. Art and Architecture in Italy, 1250 to 1400, London, Penguin Books, 1966, 2nd edn 1987 (now Yale History of Art series). ISBN 0140561285

Further reading [edit]

- Bandera Bistoletti, Sandrina, Giotto: catalogo completo dei dipinti (I gigli dell'arte; 2) Cantini, Firenze 1989. ISBN 88-7737-050-5.

- Basile, Giuseppe (a cura di), Giotto: gli affreschi della Cappella degli Scrovegni a Padova, Skira, Milano 2002. ISBN 88-8491-229-6.

- Bellosi, Luciano, La pecora di Giotto, Einaudi, Torino 1985. ISBN 88-06-58339-5.

- de Castris, Pierluigi Leone, Giotto a Napoli, Electa Napoli, Napoli 2006. ISBN 88-510-0386-half-dozen.

- Cole, Bruce, Giotto and Florentine Painting, 1280-1375. Hew York: Harper & Row. 1976. ISBN 0-06-430900-2.

- Cole, Bruce, Giotto: The Scrovegni Chapel, Padua. New York: George Braziller 1993. ISBN 0-8076-1310-X.

- Derbes, Anne and Sandona, Mark, eds., A Cambridge Companion to Giotto. Cambridge University Press 2004. ISBN 978-0-521-77007-one.

- Flores D'Arcais, Francesca, Giotto. New York: Abbeville 2012. ISBN 0789211149.

- Frugoni, Chiara, L'affare migliore di Enrico. Giotto eastward la cappella degli Scrovegni, (Saggi; 899). Einaudi, Torino 2008. ISBN 978-88-06-18462-9.

- Gioseffi, Decio, Giotto architetto, Edizioni di Comunità, Milano 1963.

- Gnudi, Cesare, Giotto, (I sommi dell'arte italiana) Martello, Milano 1958.

- Ladis, Andrew, Giotto'southward O: Narrative, Figuration, and Pictorial Ingenuity in the Loonshit Chapel, Pennsylvania State Upwardly, University Park, Pennsylvania 2009. ISBN 978-0271034072.

- Meiss, Millard, Giotto and Assisi, New York University Press 1960.

- Pisani, Giuliano. I volti segreti di Giotto. Le rivelazioni della Cappella degli Scrovegni, Rizzoli, Milano 2008; Editoriale Programma 2015, pp. 1–366, ISBN 978-8866433538.

- Ruskin, John, Giotto and His Works in Padua, London 1900 (2nd ed. 1905).

- Tintori, Leonetto, and Meiss, Millard, The Painting of the Life of St. Francis in Assisi, with Notes on the Loonshit Chapel, New York Academy Printing 1962.

- Sirén, Osvald, Giotto and Some of His Followers (English language translation by Frederic Schenck). Harvard University Press, Cambridge (Mass.) 1917.

- Wolf, Norbert, Giotto di Bondone, 1267-1337: The Renewal of Painting. Los Angeles: Taschen 2006. ISBN 978-3-8228-5160-9.

External links [edit]

- Page at Spider web Gallery of Fine art

- Giotto in Panopticon Virtual Art Gallery

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Giotto

0 Response to "Did Giotto Draw a Perfect Circle"

Post a Comment